Back in the early 2000s, radio stations didn’t just play songs because they sounded good. They played them because they had to prove the song could stick around - and that meant tracking radio add dates. These were the exact days when stations officially started spinning a new single, and for artists like Robert Hill, those dates became make-or-break moments in chart success.

What Radio Add Dates Actually Meant

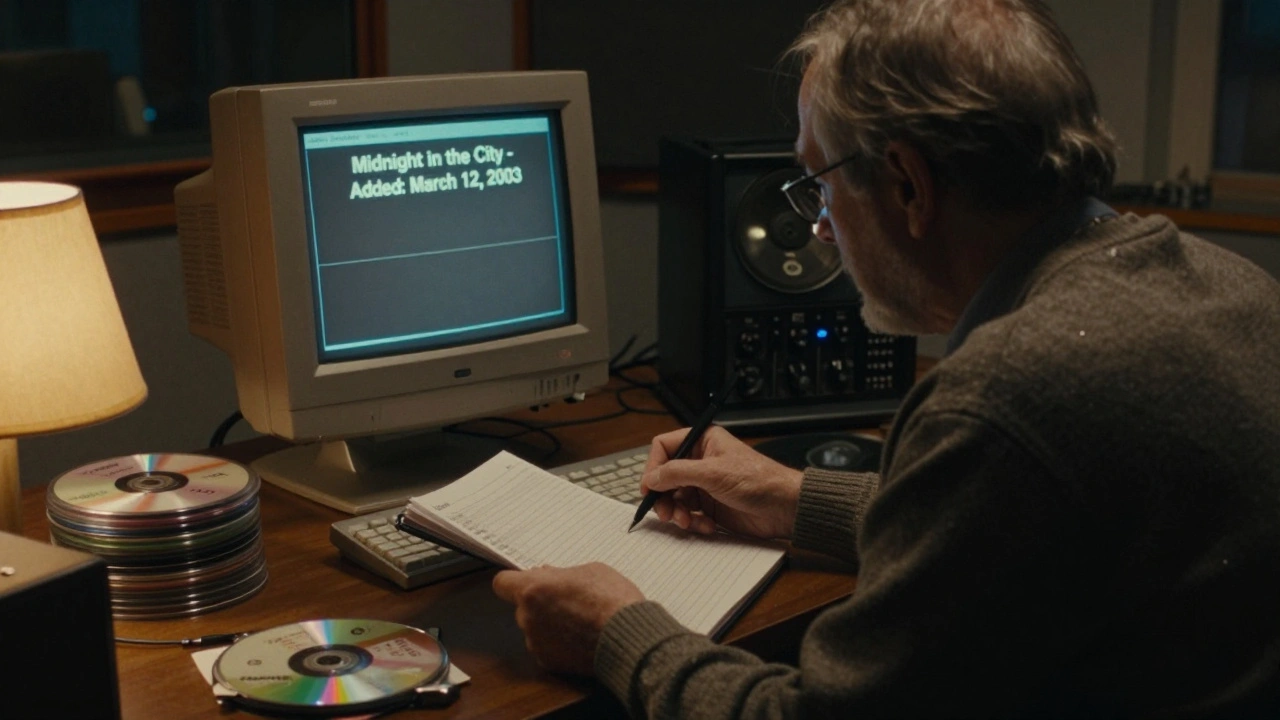

Radio add dates weren’t random. They were scheduled by record labels, often tied to promotional cycles, album drops, or even weather patterns. If a single hit the airwaves too early, it could burn out before the album dropped. Too late, and it lost momentum. For Robert Hill, his first major single, "Midnight in the City," got its official add date on March 12, 2003 - a Tuesday, which was standard for new releases. That date wasn’t chosen by chance. It was picked because it gave the song six weeks to build before the spring music festival season kicked in.

Back then, Billboard tracked adds manually. Radio stations called in their add dates to Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems (BDS), which logged every spin. No algorithms. No streaming data. Just human reports from program directors who decided whether a song was "ready." For Robert Hill, that meant his label had to convince over 120 stations across the U.S. to add "Midnight in the City" within a 14-day window. If fewer than 80 stations added it by the third week, the label would pull the plug on promotion.

How Robert Hill’s Singles Got Added

Robert Hill didn’t have a huge marketing budget. He wasn’t signed to a major label. His breakout came through independent radio promotion. His team didn’t send CDs to stations. They sent MP3s - early, clean, and tagged with metadata so DJs could preview them on their computers. That was new in 2003. Most labels still used physical promo CDs.

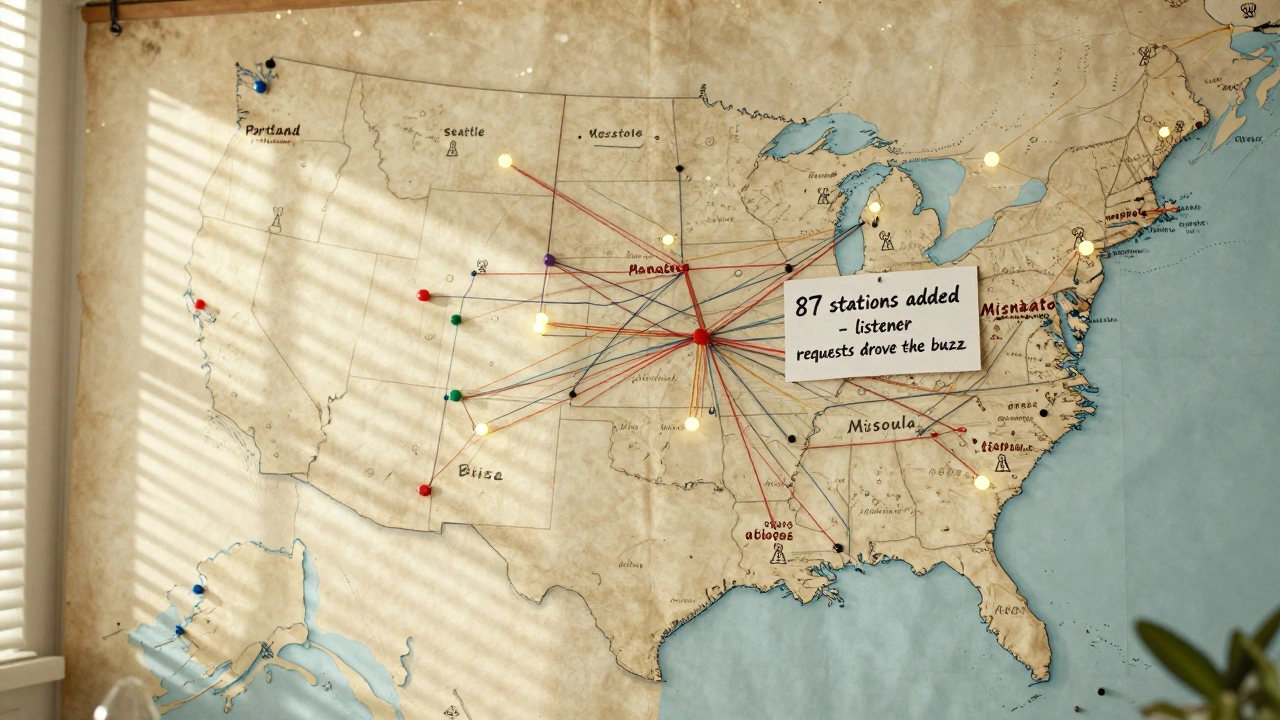

His first single, "Midnight in the City," hit 87 stations on its add date. That was below the 100-station benchmark most labels aimed for, but it was enough in the indie scene. The song climbed to No. 17 on the Billboard Adult Alternative chart by May. Why? Because stations in Portland, Seattle, and Minneapolis kept playing it - not because they were told to, but because listeners called in and asked for it.

His second single, "Cigarette Lighter," got its add date on August 5, 2004. This time, his team targeted college radio first. They knew stations like KEXP in Seattle and KURB in Eugene had already played "Midnight" 47 times in the last month. So they pitched "Cigarette Lighter" as the follow-up. Within 72 hours, 62 college stations added it. By the end of the month, 37 commercial stations followed. The song peaked at No. 12 on the same chart - higher than the first.

The Role of Regional Markets

Robert Hill’s chart success wasn’t built in New York or L.A. It was built in mid-sized cities. Portland, where the song was recorded, became a testing ground. Stations like KNRK and KUFO gave the song early spins. Listeners in Oregon and Washington started requesting it. That local buzz became a signal to national stations: "If people here are obsessed, maybe we should try it too."

By 2005, Billboard started factoring in regional add data. If a song added in three or more markets under 500,000 people, it got a "Regional Momentum" boost. Robert Hill was one of the first artists to benefit. "Cigarette Lighter" didn’t just get added - it got added in places like Boise, Reno, and Missoula. Those weren’t big markets, but they were consistent. And consistency mattered more than big-city hype.

Why Some Singles Never Made It

Not every Robert Hill single made the cut. "Broken Clock," released in 2006, had a perfect add date - October 10, 2006. But the label waited too long to send out promos. By the time stations got the track, it was already October 25. The holiday season was coming. Program directors had already locked in their playlists. "Broken Clock" got added to only 41 stations. It never charted.

That taught the team one hard lesson: add dates weren’t just about timing. They were about preparation. If you didn’t have promo materials ready 30 days before the add date, you were already behind.

How the System Changed After 2010

By 2010, radio add dates started fading. Streaming data replaced manual reporting. Spotify and Apple Music began sharing play counts. Billboard started weighting digital streams over radio spins. Robert Hill’s 2011 single, "Holding On," didn’t even have an official add date. It just went live on streaming platforms. The label didn’t call stations. They didn’t need to.

But for his first three singles - the ones that broke him - radio add dates were everything. They were the checkpoints that turned local listeners into national fans. Without those dates, "Midnight in the City" might have stayed a Portland secret. Without the follow-up push on "Cigarette Lighter," he might have faded after one hit.

What Radio Add Dates Taught Artists

Robert Hill’s rise wasn’t about luck. It was about understanding how the old system worked. He learned that:

- Adding a song to 100 stations didn’t guarantee success - consistency did.

- Smaller markets could be more powerful than big ones if they were loyal.

- Getting your song on the air was only half the battle. Keeping it there was the real test.

- Radio add dates were deadlines - not suggestions.

Even today, when playlists are algorithm-driven, those lessons still matter. If you’re an artist releasing music now, ask yourself: Are you just dropping a song - or are you building momentum? Because the old radio system taught us something simple: radio add dates didn’t make songs popular. People did. And if you can get enough people to ask for your song on the radio, the rest follows.

What is a radio add date?

A radio add date is the official day a radio station begins playing a new song regularly. It’s not when the song is first played - it’s when the station commits to adding it to its rotation, usually after testing listener response. Record labels coordinate these dates to maximize chart impact.

Why did Robert Hill’s singles succeed on radio?

His singles succeeded because they were introduced at the right time, targeted the right markets, and built organic listener demand. Stations in Portland, Seattle, and other mid-sized cities kept playing his songs because audiences requested them. That local buzz convinced national stations to add his music too.

How did radio stations decide which songs to add?

Program directors listened to promo copies, checked listener call-in requests, and tracked how often a song was played during test periods. They also considered whether the song fit their format - like adult alternative or college radio. For Robert Hill, his acoustic-driven sound and relatable lyrics made him a natural fit for stations that valued authenticity over polish.

Did Robert Hill have a record label?

He started with an independent label, but never signed with a major. His early success came from grassroots promotion - sending MP3s to indie and college stations, building relationships with DJs, and letting listener feedback drive the momentum. His label didn’t have big ad budgets, but they had smart timing and deep regional knowledge.

Are radio add dates still important today?

Not in the same way. Today, streaming platforms and algorithm-driven playlists determine a song’s success more than radio adds. But for artists breaking into traditional formats - like country, classic rock, or public radio - add dates still matter. Stations still track listener demand, and a strong regional push can lead to national rotation, just like it did for Robert Hill.