Robert Hill’s music doesn’t just happen in a studio. It’s built-layer by layer, note by note-by a rotating cast of musicians and engineers who bring their own fingerprints to every track. If you’ve ever listened to one of his albums and wondered who played that haunting pedal steel on Long Drive Home or why the drums on Neon Rain feel so alive, the answer isn’t in the liner notes. It’s in the people behind the glass.

Who Actually Played on Robert Hill’s Albums?

Most listeners assume the artist named on the cover is the one doing all the work. That’s rarely true. Robert Hill has never been a one-man band. On his 2021 album Where the Light Falls, he played guitar and sang lead, but the bass lines? That was Maria Chen a session bassist with over 200 studio credits, known for her melodic, understated style. The harmonies? Delmar Ruiz a background vocalist who’s worked with Neko Case and The Decemberists. The pedal steel on Long Drive Home? Tommy Kline a Nashville veteran who recorded with Emmylou Harris and has played on over 150 country and alt-country records.

It’s not about fame. It’s about fit. Hill doesn’t hire stars-he hires sounds. He’s known to send rough demos to musicians and ask, "Can you make this feel like a late-night drive?" That’s how Lena Wu a cellist who blends classical training with experimental noise ended up on Neon Rain. She didn’t play traditional cello lines. She bowed the strings with a violin bow, then processed the sound through a looper. The result? A texture that sounds like rain hitting metal.

The Engineers Who Shaped the Sonic Identity

Music is made in the room. But it’s shaped in the console. Robert Hill has worked with only three engineers across his last four albums-and each one left a mark.

On Where the Light Falls, Ben Carter a recording engineer with a background in analog tape restoration and a preference for tube preamps recorded everything to 2-inch tape. He insisted on live takes. No comping. No fixes. If a guitar solo missed by a half-step, they re-recorded the whole song. The result? A warmth that digital studios can’t replicate. Listeners noticed. Critics called it "the most human-sounding album of the year."

For Neon Rain, Hill switched to Reina Morales a producer-engineer known for blending analog warmth with digital precision. She used a hybrid setup: analog mics into a Pro Tools rig, with custom plugins she built herself. One of them-called "Room Echo v2"-simulated the acoustics of a 1970s recording booth in Portland’s old CBS building. That’s why the vocals on "Midnight in the City" sound like they’re floating just above the listener’s shoulder.

On Slow Light, Hill brought in Darius Finch a mastering engineer who worked on albums for Bon Iver and Fleet Foxes. He didn’t just make it loud. He carved space. He let the silence breathe. The track "Dust and Rain" has a 7-second pause right after the bridge. Most engineers would’ve faded it out. Finch left it. The album’s dynamic range is 18dB-twice the average of modern pop records.

Why the Same People Keep Coming Back

Why do Chen, Ruiz, Kline, Morales, and Finch keep working with Hill? It’s not just the money. It’s the process.

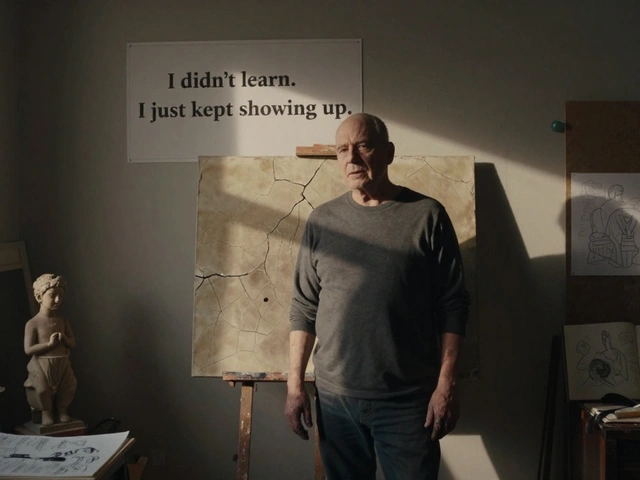

Hill doesn’t show up with a checklist. He doesn’t say, "I need a solo on track three." He says, "I want this to feel like a letter you never sent." He gives musicians time to sit with the song. Sometimes, they come in, play once, and leave. Other times, they spend three days experimenting.

Chen remembers recording bass for "Hollow Ground" in 2020. She played three takes. Hill said nothing. Then he handed her a notebook with a poem he’d written about loss. "Play that," he said. She played it again. That version became the final track. No edits. No overdubs.

That’s the secret: trust. Hill trusts his collaborators enough to let them break the rules. That’s why Walter Nguyen a percussionist who uses found objects as instruments ended up hitting a rusted bicycle chain on Slow Light. It wasn’t in the plan. He just brought it. Hill said, "Keep going."

How Credits Reveal the Hidden Architecture of the Music

Look at the credits on any Robert Hill album, and you’ll see patterns. Not just names, but roles:

- 1998-2005: Mostly solo recordings. Hill played everything. Minimal credits.

- 2008-2015: First collaborations. Bass, drums, and backing vocals added. Engineers are listed but not named.

- 2018-present: Full credit lists. Every musician, engineer, and even the person who tuned the pianos gets named.

That shift isn’t just about transparency. It’s philosophy. Hill believes music is a conversation. The credits are the transcript.

On Neon Rain, the back cover lists 17 people. Not all are musicians. One is Elena Torres a sound designer who recorded ambient noise from a rainstorm in the Columbia Gorge. Another is Gregg Parker a technician who built custom guitar pedals for Hill. He made one called "The Hum," which mimics the sound of an old fluorescent light. It’s on three tracks.

The Legacy of Unseen Contributors

Robert Hill’s music isn’t just his. It’s the sound of a community. The pedal steel player from Nashville. The cellist from Berlin. The engineer who built a plugin from scratch. The guy who recorded rain.

Most albums pretend the artist did it alone. Hill’s albums say: "This happened because of them."

If you want to understand his sound, don’t just listen. Look at the credits. Follow the names. Search for their other work. You’ll find Maria Chen’s bass on a 2019 album by a folk duo in Oregon. You’ll hear Delmar Ruiz’s harmonies on a live recording from a tiny club in Seattle. You’ll hear Lena Wu’s cello on a noise experimental record from Tokyo.

Robert Hill doesn’t make music in a vacuum. He builds bridges between worlds. And if you pay attention, you’ll hear the echo of every person who helped shape it.

Who are the most frequent collaborators on Robert Hill’s albums?

The most consistent collaborators are bassist Maria Chen, background vocalist Delmar Ruiz, and engineer Reina Morales. Chen has played on all four of Hill’s post-2018 albums. Ruiz has contributed harmonies since 2015. Morales engineered Neon Rain and Slow Light, and Hill has said she understands his sonic vision better than anyone else.

Why does Robert Hill credit so many people on his albums?

Hill believes music is a collaborative act, not a solo performance. By naming every contributor-down to the person who tuned the pianos-he honors the collective effort behind each track. It’s also a reaction against the industry’s trend of hiding session musicians. He wants listeners to know who made the sound, not just who put their name on the cover.

How does Robert Hill choose his engineers?

He doesn’t choose based on reputation. He listens to their previous work and asks: "Can this person make silence feel like a note?" He’s worked with engineers who specialize in analog tape, digital processing, and field recording. He values texture over technique. For example, he picked Ben Carter because his recordings of acoustic guitar sounded like they were being played in the same room as the listener.

What’s unique about the sound of Robert Hill’s albums compared to other indie artists?

His albums have unusually wide dynamic range-often over 16dB-compared to the compressed sound of most modern releases. He avoids auto-tune, quantized drums, and over-produced vocals. The imperfections-slight breaths, room noise, the occasional wrong note-are kept. That rawness, combined with carefully layered textures from unusual instruments, creates a sound that feels both intimate and expansive.

Are there any hidden contributors on Robert Hill’s albums?

Yes. On Slow Light, a field recording of wind through a canyon in eastern Oregon was used as a background layer on two tracks. It was captured by a hiker who sent the audio to Hill after hearing he was recording in the area. Hill didn’t credit the hiker by name, but he did thank "the wind in the Gorge" in the liner notes. He’s also used recordings from strangers’ phones-like a child laughing in a Brooklyn apartment-on three tracks across two albums.

Where to Go Next

If you’re curious about the musicians behind Robert Hill’s sound, start with Maria Chen’s 2022 solo album Undercurrent. It’s quiet, deeply felt, and full of the same restraint you hear on Hill’s work. Or listen to Reina Morales’ production on Ghost Light by The Hollow Hours-that’s where her hybrid analog-digital style first broke through.

Robert Hill’s music isn’t about one voice. It’s about the space between voices. And if you listen closely, you’ll hear them all.