Robert Hill doesn’t just play the blues-he digs into its bones. While many gospel blues artists lean into spiritual uplift, Hill’s work pulls at the raw, aching edges of faith, loss, and survival. If you’ve ever listened to a gospel blues record and felt like something was missing-a deeper grit, a more personal confession-you’ve probably been hearing the difference between Hill and his peers.

What Makes Gospel Blues Different?

Gospel blues isn’t just blues with a choir in the background. It’s a fusion born in the Black churches of the American South, where spirituals met the slide guitar and the moan of the harmonica. Artists like Washington Phillips, Blind Willie Johnson, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe turned hymns into haunting, earthy songs. Their music wasn’t meant for Sunday morning alone-it was for Saturday night, for broken backs, for prayers whispered in the dark.

Most gospel blues artists used their sound to offer hope. Johnson’s Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground doesn’t just describe suffering-it makes you feel the weight of it, then lifts you with a quiet, unshakable faith. That’s the pattern: pain, then redemption.

Robert Hill’s Twist on the Tradition

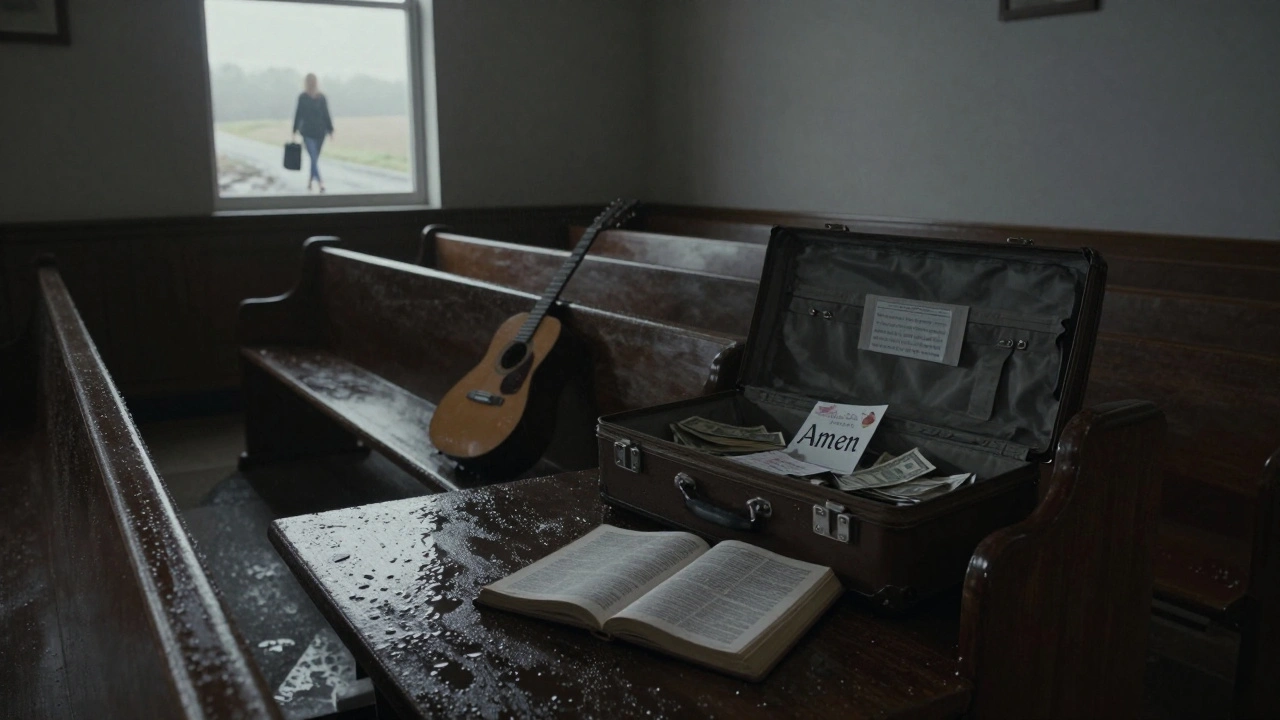

Hill breaks that pattern. His 2022 album Where the Lord Ain’t opens with a track called Preacher’s Wife Left With the Preacher’s Money. No redemption. No heavenly chorus. Just a woman walking away from a church with a suitcase and a pocketful of cash. The slide guitar weeps, but the drums don’t let up. There’s no resolution.

Where others sing I’ll fly away, Hill sings I’m still here. His lyrics don’t ask for salvation-they demand truth. In Church Steps, he describes a man who prays every night outside his old church, not because he believes, but because he remembers what it felt like to believe. That’s not gospel blues. That’s gospel after the blues.

Contrasting Themes: Faith, Doubt, and Survival

Let’s compare three core themes across Hill and his peers.

| Theme | Traditional Gospel Blues Artists | Robert Hill |

|---|---|---|

| Faith | Unshakable, divine, communal | Questioning, solitary, fading |

| Redemption | Guaranteed through prayer or sacrifice | Uncertain, sometimes absent |

| Community | Church, family, shared suffering | Isolation, broken ties, silence |

| Music Style | Call-and-response, handclaps, organ | Minimalist, sparse drums, lone slide |

| Ending Tone | Hopeful, ascending | Open-ended, unresolved |

Hill’s approach isn’t a rejection of gospel blues-it’s a continuation of it, pushed into a new century. Where Johnson’s voice cracked with divine urgency, Hill’s voice is tired. He doesn’t sing like he’s waiting for heaven. He sings like he’s waiting for someone to ask him if he’s okay.

Why This Matters Now

In 2026, gospel blues is often sanitized. Streaming playlists label it as “inspirational,” “uplifting,” or “spiritual.” But real gospel blues was never about comfort. It was about survival. Hill reminds us of that. He’s not trying to bring people back to church-he’s trying to bring church back to the people who lost it.

His 2024 live recording in a shuttered Baptist church in Jackson, Mississippi, went viral not because it was pretty, but because it was honest. No microphones. No amplifiers. Just a man, a guitar, and the echo of a building that once held a thousand prayers. When he sings I don’t need no angel to carry me home, you hear not defiance, but exhaustion. And that’s the point.

Who Should Listen to Robert Hill?

If you’re drawn to artists like Leonard Cohen, Townes Van Zandt, or even early Nick Cave, you’ll find something familiar in Hill. He doesn’t preach. He doesn’t perform. He bears witness.

He’s not for people who want to feel better. He’s for people who want to feel seen.

His audience isn’t the faithful. It’s the forgotten. The ones who still go to church on Sundays but don’t kneel anymore. The ones who still say grace before meals but don’t believe in miracles. The ones who still hum hymns in the shower because it’s the only thing that hasn’t left them.

The Legacy of a New Kind of Gospel

Robert Hill doesn’t replace the giants of gospel blues. He adds a new verse to their song. Where Blind Willie Johnson sang about heaven, Hill sings about the silence between prayers. Where Sister Rosetta Tharpe made the guitar scream with joy, Hill makes it whisper with doubt.

His music doesn’t offer answers. It asks better questions. And in a world that’s never been louder, that’s the rarest kind of gospel.

Is Robert Hill considered a gospel blues artist?

Yes, but not in the traditional sense. Hill uses the musical structure and instrumentation of gospel blues-slide guitar, call-and-response phrasing, spiritual lyrics-but subverts its core message. While classic gospel blues seeks redemption, Hill explores abandonment, doubt, and quiet endurance. He’s a gospel blues artist who writes about what happens after the hymns stop.

How does Robert Hill’s music differ from Blind Willie Johnson’s?

Blind Willie Johnson’s music is rooted in divine hope. Even in his darkest songs, like Jesus Is Coming Soon, there’s a sense of imminent salvation. Hill’s music, by contrast, is about waiting for something that may never come. Johnson’s voice sounds like it’s speaking to God. Hill’s sounds like it’s speaking to the empty space where God used to be. Musically, Johnson layered harmonies and used heavy reverb. Hill strips everything down-just voice, slide, and a single drum.

Are there other artists similar to Robert Hill?

A few. John Fahey’s later work, especially The Way Young Lovers Die, shares Hill’s sparse, melancholic tone. Jason Molina’s Songs: Ohia records, particularly Ghost Tropic, echo Hill’s themes of isolation and fading faith. Even modern artists like Marissa Nadler and William Tyler touch similar emotional ground, though they don’t use gospel blues instrumentation. Hill’s closest peer might be the late Mississippi John Hurt-quiet, deeply personal, and unafraid to leave questions unanswered.

Why is Robert Hill’s work gaining attention now?

Because people are tired of curated spirituality. In an age of influencers preaching self-help and digital revival meetings, Hill’s raw, unpolished honesty cuts through. His 2024 live album, recorded in an abandoned church, has over 2 million streams-not because it’s pretty, but because it’s real. Listeners are drawn to his refusal to offer easy answers. He doesn’t heal. He just shows up.

Can you recommend a starting point for new listeners?

Start with the track Church Steps from his 2022 album Where the Lord Ain’t. It’s five minutes long, features no lyrics after the first verse, and relies entirely on the emotional weight of a single repeating slide guitar riff. It’s not about what’s said-it’s about what’s left unsaid. That’s Robert Hill in one song.